Titles by Ludlum and Yerby

As a freelancer on assignment with New York City trade-book publishers, I edited a number of bestselling and award-winning novels, including a title by Robert Ludlum and another by Frank Yerby. In those days, manuscript editors worked with red pencil on hard copy, attaching queries and comments to the pages with stick-on "flags."

The Chancellor Manuscript by Robert Ludlum

|

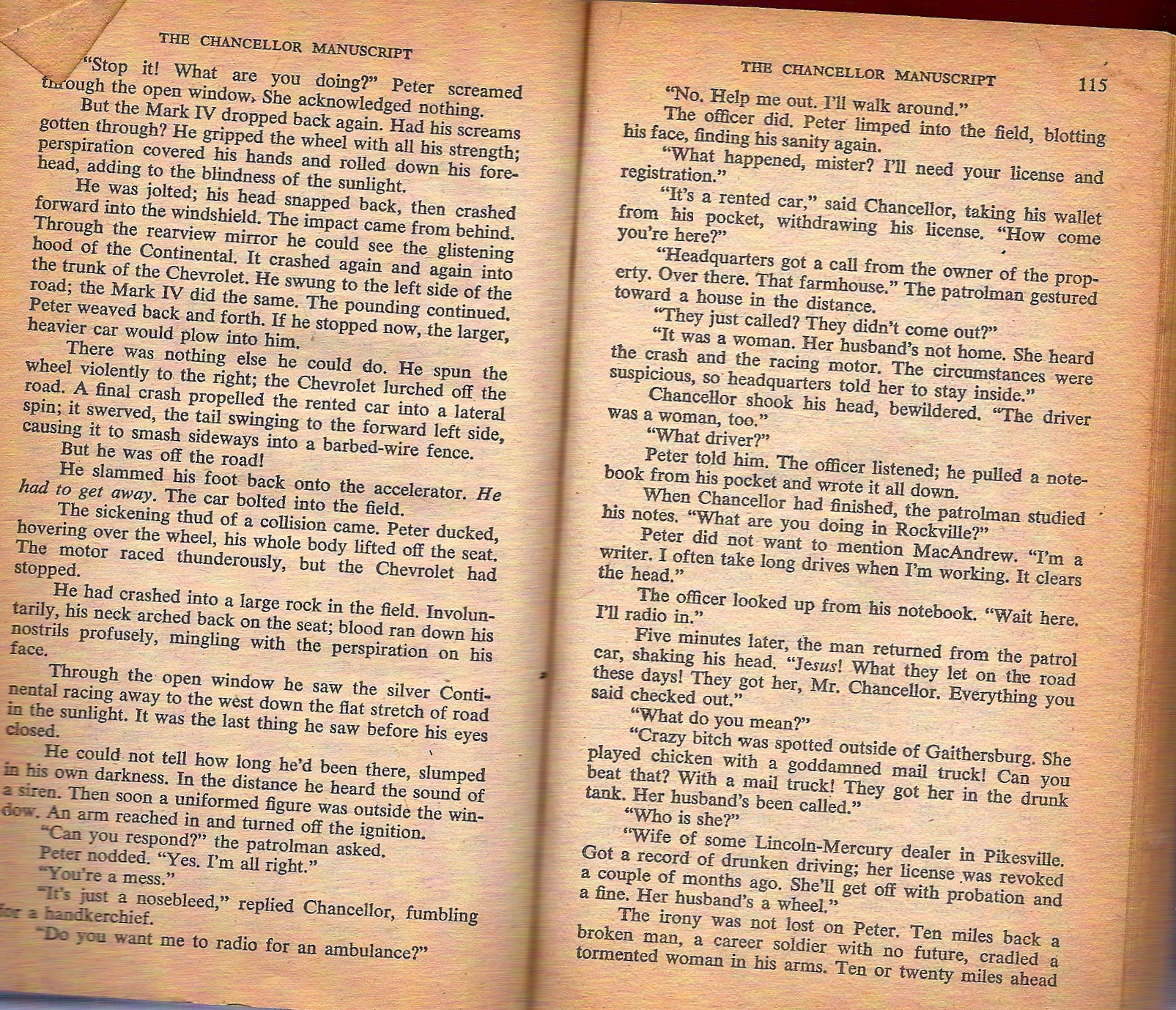

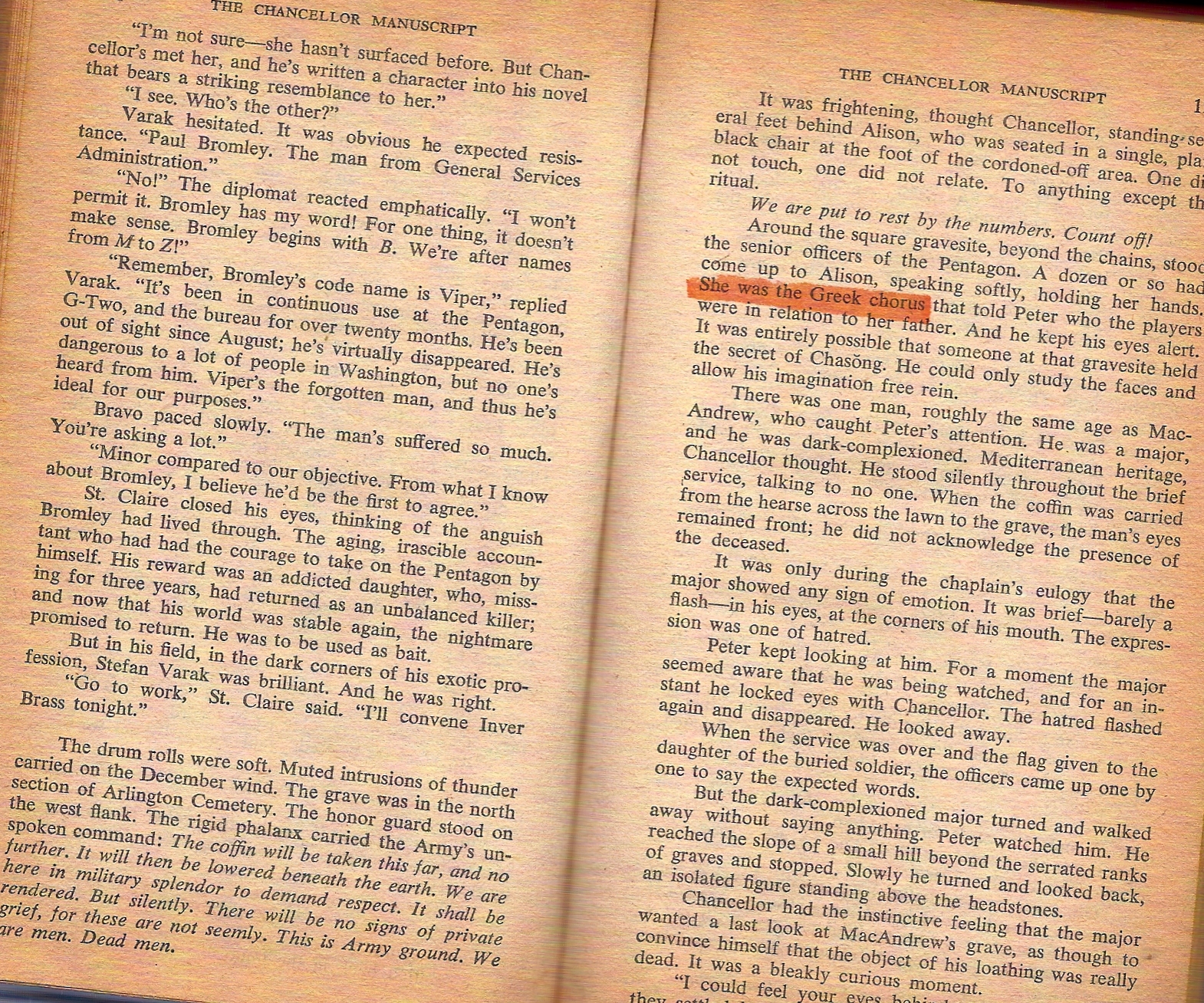

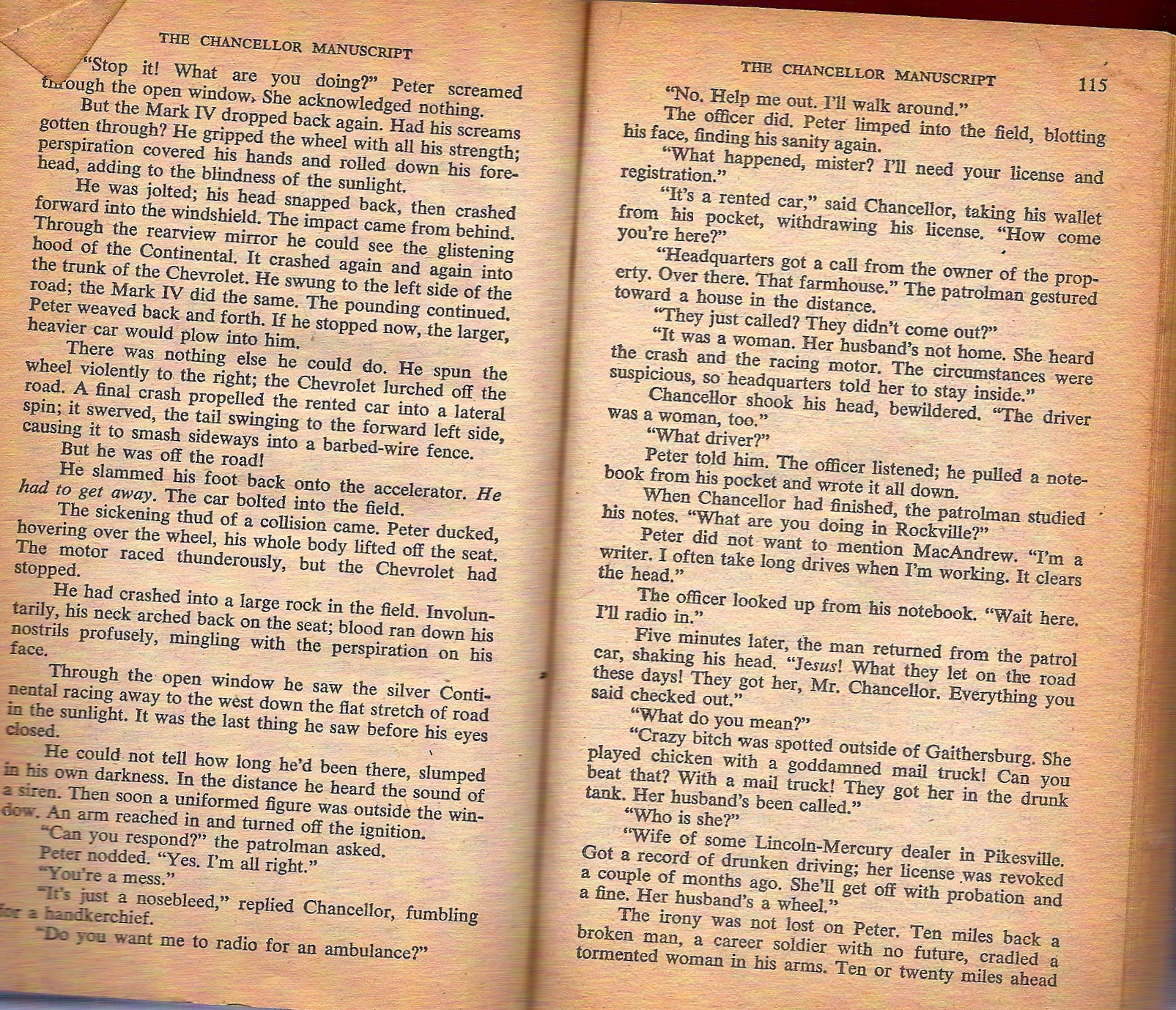

This novel was published in 1977 by Dial Press. According to the New York Times Book Review, it "exerts a riveting appeal, as it seems to justify our worst nightmares of what really goes on in the so-called Intelligence Community in Washington." This author spins a spell-binding tale, but he tends to be nonchalant about details, which is why each of his potboilers needs a nitpicking editor. I had to fetch a map of Washington, DC, to discover that he had a car chase turning at an intersection of two well-known streets that are actually parallel. Also, he had a description of the hero's head jolting forward to hit the windshield when his car was struck from behind; he accepted my revision that the hero's head would first snap back before jolting forward (see the third paragraph on page 114).

|

|

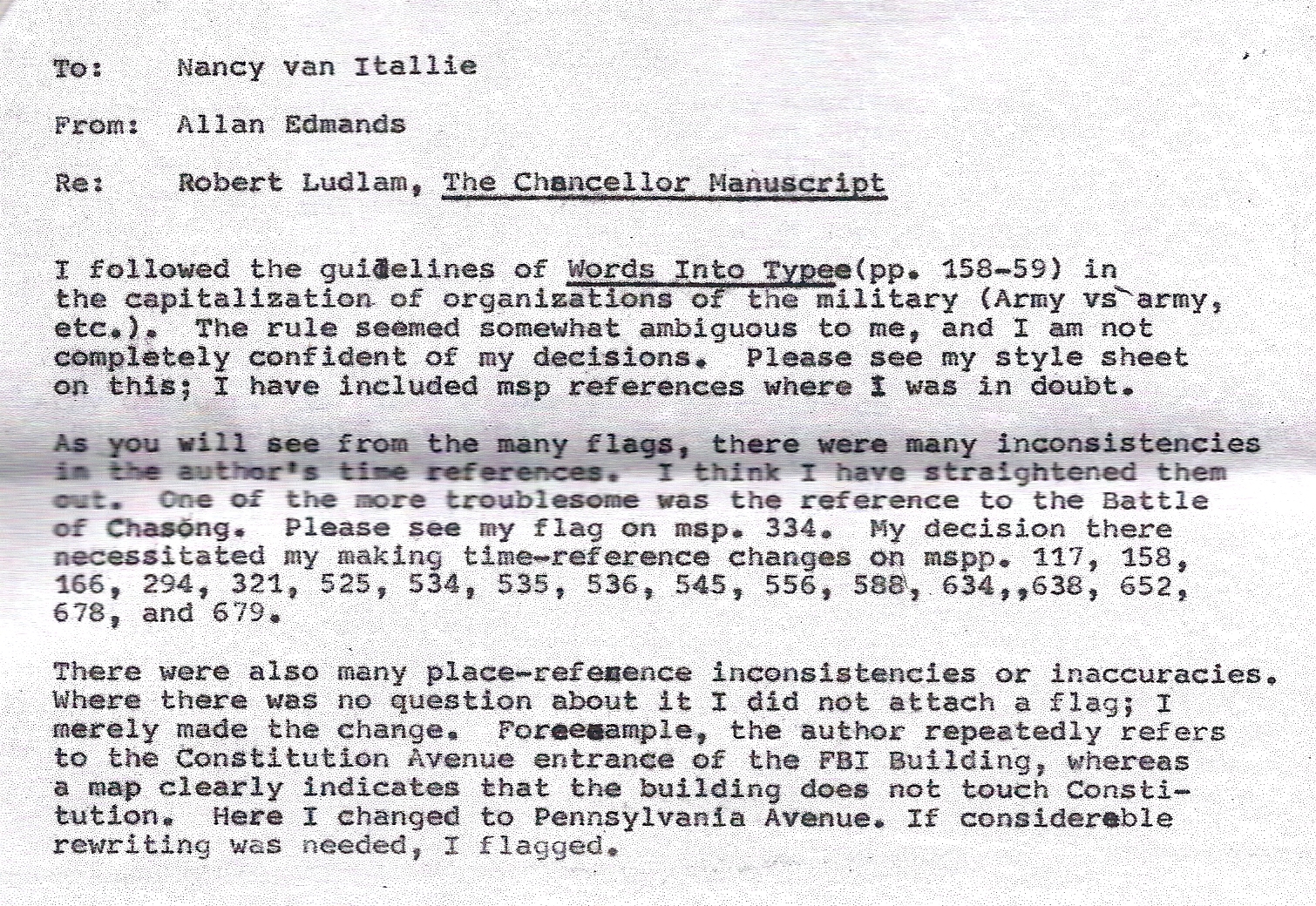

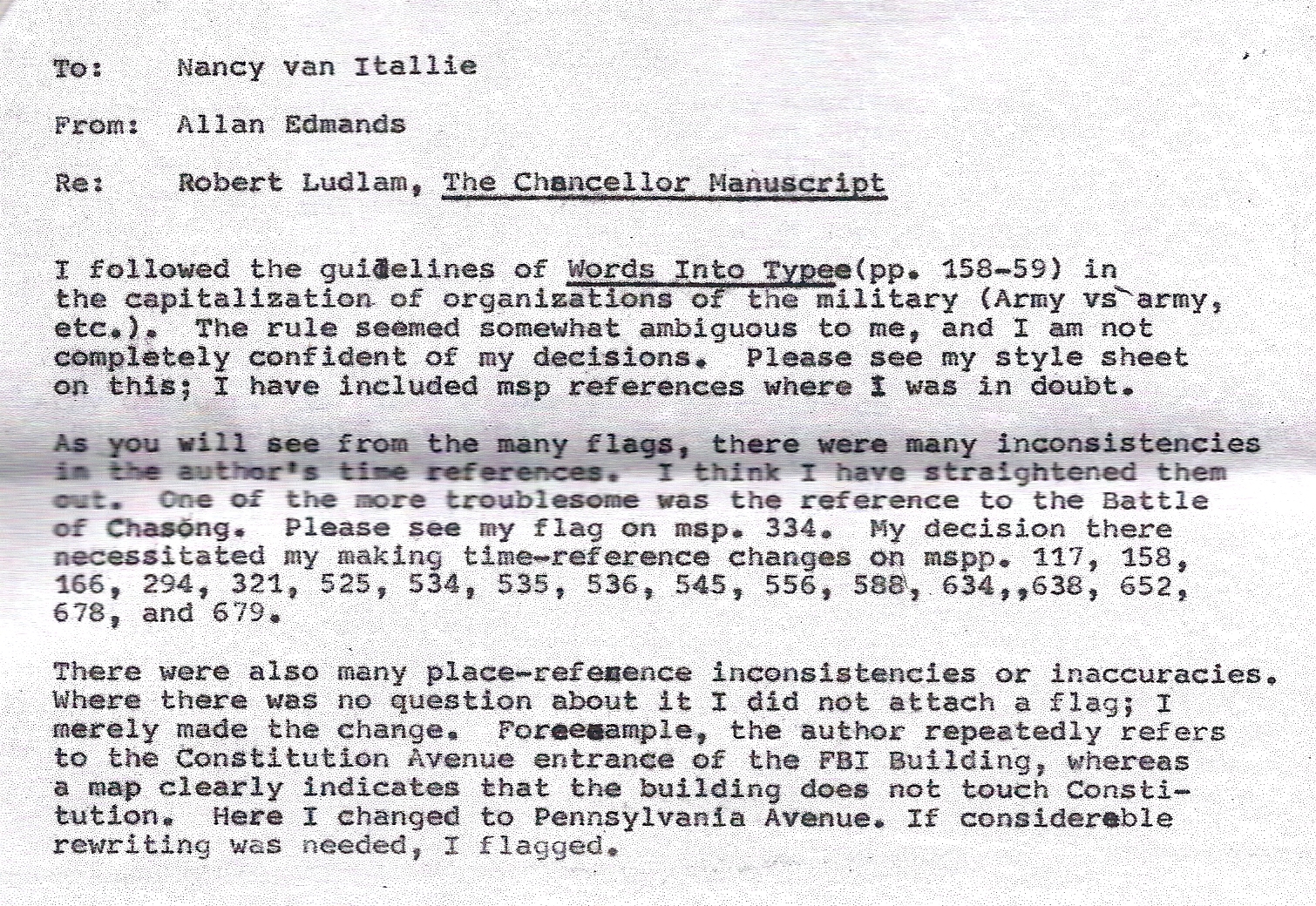

Here is the cover letter (typewritten, the overtyped "mistakes" are not on the original) I sent to the senior editor at Dial who had given me the assignment: |

|

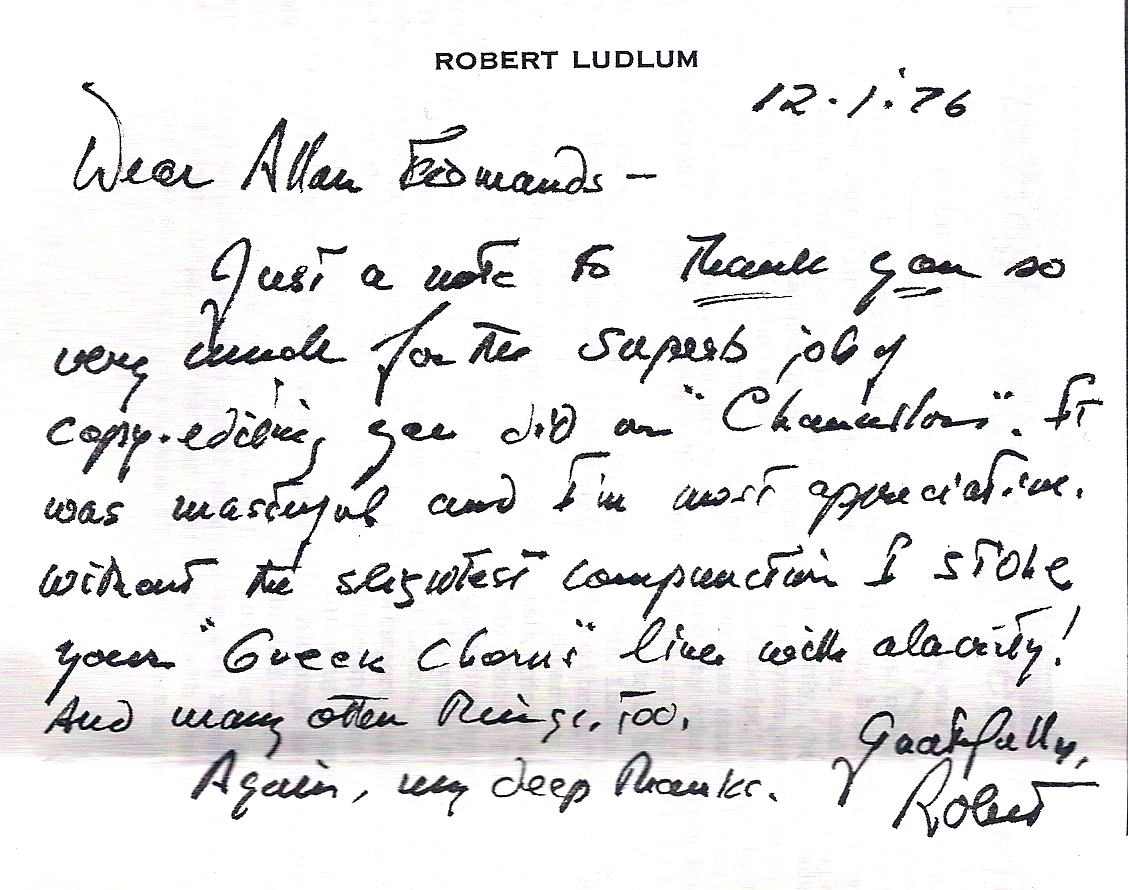

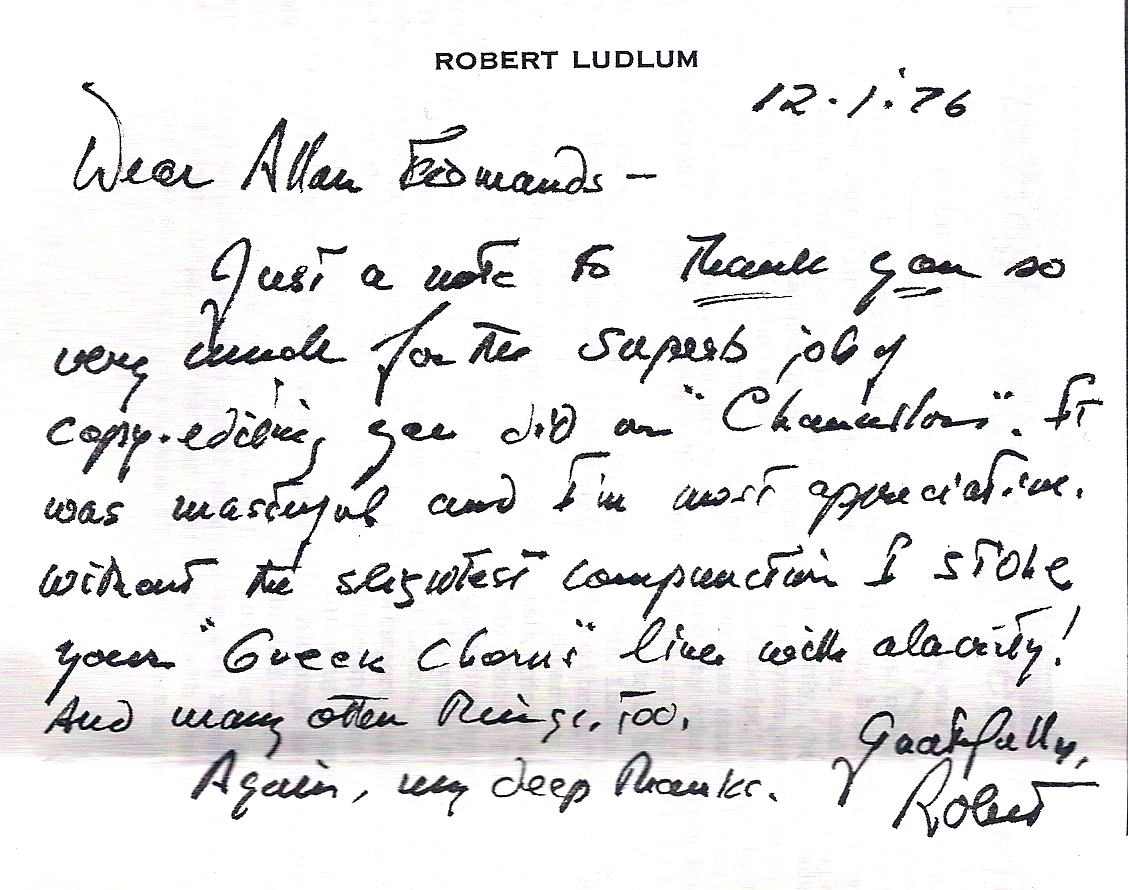

The author sent me a card with his appreciation: |

|

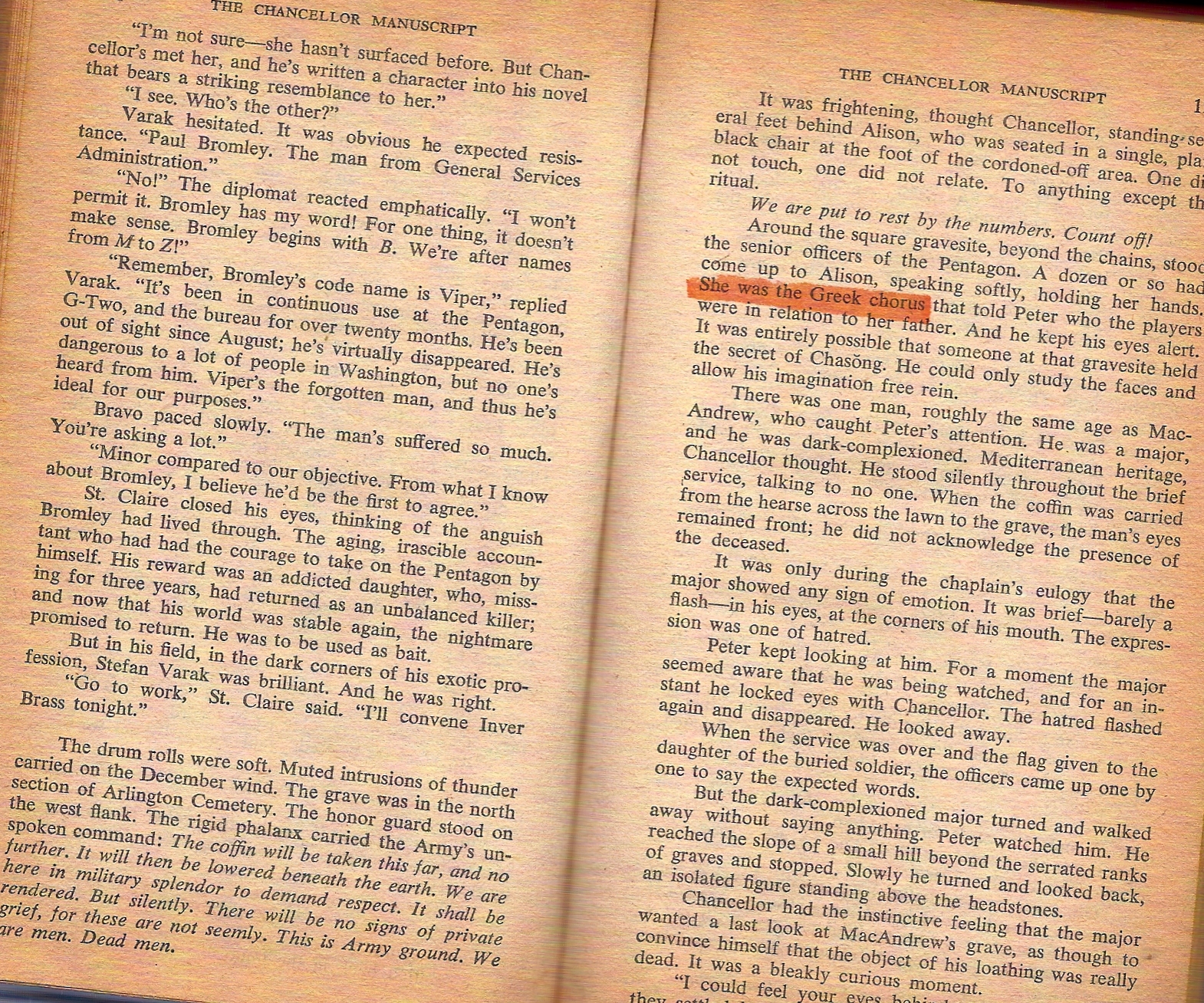

The highlight shows what he "stole" from me with alacrity: |

|

Darkness at Ingraham's Crest by Frank Yerby

|

This novel was published in 1979 by Alfred A. Knopf. I was alerted by the senior editor that this author was very touchy with anyone messing with his prose. With his hard-copy manuscript, the irascible (and unabashedly sexist) Mr. Yerby included this submission note to the publisher, beginning with a plea for help in correcting a slip-up of his own:

A NOTE TO PROOF'READERS

Throughout this book there is one consistent spelling error: Pamela Ingraham's six year old daughter DEIRDRE, so named after "Deidre of the Sorrows" from the Irish legends, has her name spelled, or rather mis-spelled Dierdre, i.e. with the positions of the e and the i reversed. Unfortunately I did not detect this until the whole thousand odd pages of the manuscript had been typed.

This rest of author Yerby's note, however, is a stern warning—even a threat:

|

I have deliberately used the Spanish spellings "Mulato" and "Mulata" throughout, for two reasons: First to retain the very useful sex distinction of the Spanish, and second because I find the Anglo-Saxon linguistic arrogance intolerable. If you're going to borrow from some other language (as the words Negro, Mulato, etc were so borrowed from either Spanish or Portuguese) have the elementary courtesy to spell them right. Hence Mulato and Mulata with one t. Of course I realize a people who will change the lovely, singing sound of the Italian city Livorno to Leghorn are capable of anything, but in this work I don't have to put up with this nonsense, and I won't.

To those bright-eyed little Darlings in Juris Jurjevic's office who are forever correcting my grammar and "improving" my style into total illegibility: Girl Babies, English hasn't any grammar. Up until about 1066, before which it was still Anglo Saxon and went like this: "Ich theo tham Mon im theot feold-" (I saw that man in that field), it did have a grammar. In fact it had a singular, a dual, and a plural, and strong, weak, and mixed declension of adjectives as in modern German. But 1066, William the Conqueror arrived, imposed Norman (bad to god awful) French on England, and left English in the horny hands of Peasants like me. After Chaucer modern English emerged, totally bereft of anything remotely ressembling [sic] a grammar. But in 1848, a Latin Scholar and a Mathematician discovered that English had no grammar, so he sat down and wrote one by grafting the rules of Ciceronian Latin - a highly inflected language, upon English, a totally destributive [sic] language, with the result that bright eyed little girls have seen fit to fornicate up the prose of past masters of English ever since on the basis of rules that make no sense at all.

Or as Winston Churchill said (much too politely!) to his secretary when the little Darling pointed out to one of the greatest prose stylists of all time that he couldn't end a sentence with a preposition: "This is a piece of arrant pedantry up with which I will not put!"

So hear this: If anybody, ever again does to the prose I've spent sixty two years learning how to write what was done to my bullfight scene in HAIL THE CONQUERING HERO, I shall arrive by Jet, armed with a hairbrush to be applied- Male Chauvinist Porker that I cheerfully am! - to the exact physical location of female brains!

NOTE TO EDITORS, AGENTS ET AL:

I know what newsprint costs, Ditto Paper. Ditto Labor. This book is as long as it had to be. It has not one surplus word. If it's too long for you, reject it outright. I'll cheerfully take it elsewhere.

FGY

I took a light hand with his manuscript, but I still found and corrected many infelicities that would have been embarrassing to him if they had been published. Here is my cover letter to the senior editor, Johanna Tani:

Herewith the manuscript as unchanged as possible. Most of my red marks are for spec'ing em dashes and differentiating for the printer open single quotes (‘) and apostrophes (’), since I realized that the typeface in the Yerby novel you sent me did not distinguish them. There are also numerous changes, which we discussed on the phone, to enforce consistency in the author's capitalization of common nouns; these are justified in the margin with my "for consist." or "for consis" (inconsistent, I know) circled remarks. Although I have combed through the manuscript in my going-over cleanup, there may still be some I have overlooked. The problem is that I did not record in my style sheet every single common noun that was l.c. on first encounter, knowing that you needed the book back this autumn. Then--surprise!--some 114 pages later the word would be u.c. five or six times in a row, indicating the author's preference, I presume. Now where was that l.c. first instance??? [Remember: this is back in the hard-copy days] The same applies for variant spellings and treatment of dialect, of course.

Still, the book is as untouched as possible: author's commas sometimes separate subject from verb and verb from object; I did not insert commas to set off address or clauses or years (from month and day) or states (from cities). I believe I altered author's punctuation style (quite inconsistent) only when serious ambiguity or outright confusion would otherwise confront the reader; in all such cases there are my abbreviated justifications in the margin.

The following variations, all in this one manuscript, were particularly troublesome: hoo-doo, Hoo-doo, Hoo-Doo, hoo doo, Hoo Doo, Voo Doo, Voodoo, Vudu, Vudu, Hoo Doo Man, Hoo-doo man, Vuduism, Voodooism, and more... I was able to discern some slight regularity according to the speaker, however, and you can see my solution in my style sheet.

As you forewarned, the book was an exercise in restraint. As a result of my work, it is in a Limbo between "just as he has written it, right down to the last comma" and copyedited according to the style books with an overall style (author's choice wherever possible) in mind. Please let me know reactions to it.

Unlike Ludlum, Mr. Yerby didn't send me a card, but he told the senior editor that mine was the best edit he had ever been "subjected to."

|

Back to the web version of the résumé

or here is the printable (PDF) version.

For more information, contact allan@thewordsman.com

|